Comedies and Proverbs

KD seminar by prof. Line-Gry Hørup

22.10 – 13.2 2024

Outcome:

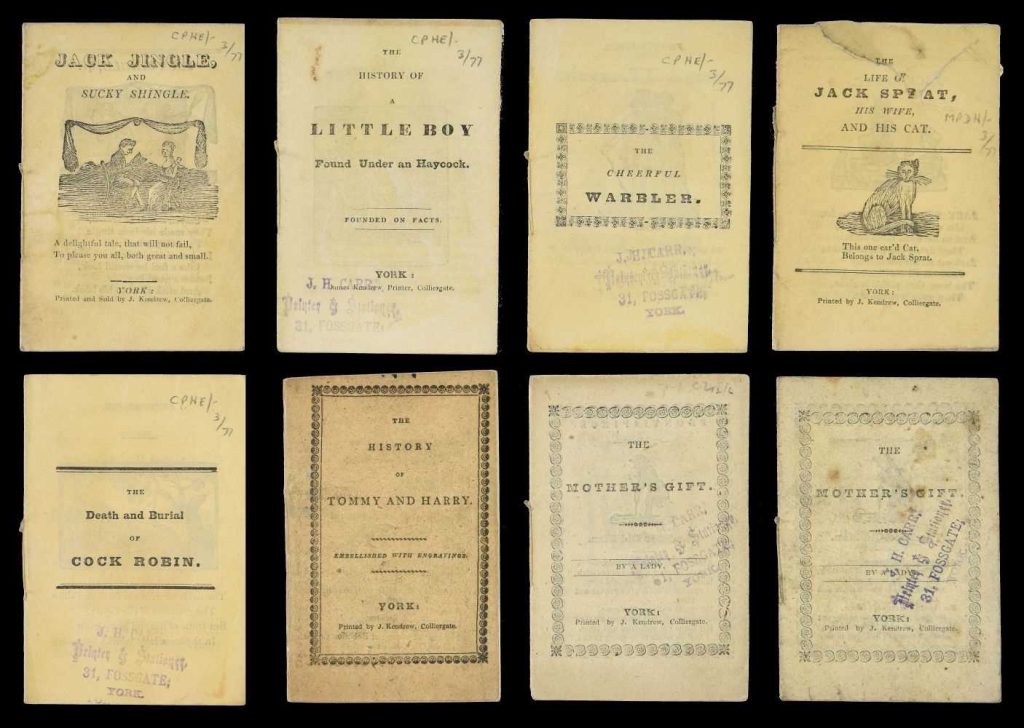

#1 One final micro chapbook length

manuscript(11x14cm 8pp) on the question:

“What enables literary quality?”

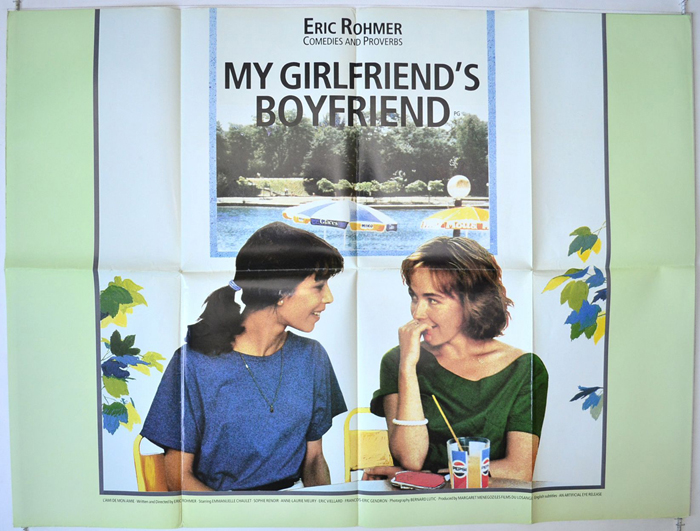

#2 A film review (Rohmer)

#3 A sentence of translation (Bresson)

Description:

The seminar will focus on the interpretation of “literariness” – a definition applicable to any artistic field – and in this particular case, examined within a film cycle by French director Èric Rohmer(1920-2010). From the beginning of his career, Rohmer took the position of a critical writer, and declared that cinema is not only a new language, but also its own language, an ambitious and vivid form of expression.

Rohmer’s literary models of choice are rather simple – such as a moral tale or a fairy tale – by contrast, the content of his films rely on more complex writing such as William Shakespeare and Henrich von Kleist. Between 1981 and 1987 he made six films each structured by a proverb. The series presents a cascade of dispirited characters caught in some sort of escalation or misunderstanding, driven by either chance or choice. A proverb exhibits a few literary functions, one could be simply a kind of “truth” meant to be repeated and spread via a riddle-like sentence, which has wrapped its content neatly in a single memorable unit. Another, is that proverbs are self-contained, like small pictures they stem from formulaic language, meaning: “a sequence which is, or seems to be, prefabricated: that is, stored and retrieved whole from memory at the time of use.”

Literariness seems to promise some kind of artistic independence, perhaps fostered by the established more honourable quality of a novel, and a central character trade for Rohmer’s cinematic language. From a literary perspective, WHAT is said is never so important as HOW it is said in the final work. By training our eyes to spot this particular quality, we might be able to see (and apply) it elsewhere.

What inspires me to asses these works as a whole, is the fact that Rohmer was part of a moment in cinema history that managed to solidify a discourse – a task graphic design is still to accomplish.

Litterature:

– Robert Bresson: Notes sure le cinématographe (physical copy at HfG)

– Brian Dillion: Suppose a Sentence (physical copy at HfG)

– Éric Rohmer: Le celluloïd et le marbre (open w. Adobe Digital Edition)

– Another Gaze Magazine: #1-5 (open w. password in Adobe Reader)

Schedule and Watch List:

Seminar 1 / 22.10 / 16:00-21:00 / Room 341 + Kino

(lecture, screening, assignment #1, #3)

The Aviator’s Wife

(1981) 104 min.

“It is impossible to think about nothing.”

A Good Marriage

(1982) 98 min.

“Can anyone refrain from building castles in Spain?”

Seminar 2 / 7.11 / 9:00-14:30 / Kino

(translation reading, screening)

Pauline at the Beach

(1983) 94 min.

“The one who talks too much will hurt themself.” 94 min.

Full Moon in Paris

(1984) 102 min.

“The one who has two women loses their soul, the one who has two houses loses their mind.”

Seminar 3 / 19.11 / 10:00-16:00 / Kino + Room 222

(lecture, screening, reading, assignment #2-#1)

The Green Ray

(1986) 98 min.

“Ah, for the days/that set our hearts ablaze”

My Girlfriend’s Boyfriend (1987)

“My friends’ friends are my friends.” 103 min.

Seminar 4 / 3.12 / 14:30-20:00 / Room 222

(midway-mark: group talks on ideas for assignment #1)

Seminar 5 / 17.12 / 10:00-16:00 / Room 222

(DEADLINE: present finished assignment #2)

{ Christmas Break }

Seminar 6 / 7.1 / 12:00 / E-mail

(DEADLINE: turn in first draft of chapbook as a doublesided pdf)

Seminar 7 / 23.1 / 10:00-16:00 / Room 216

(individual response on chapbook w. Paul Bailey, schedule TBD)

Bonus / 4.2 / 12:00 / E-mail

(Option: turn in second draft of chapbook as a doublesided pdf)

Seminar 8 / 12.2 / 10:00-14:00 / Room 216

(DEADLINE: hand in final chapbook, plan presentation

+ cross-over screening with Frederik Worm)

The Encyclopedia Brittanica tells us that “most chapbooks were 14 by 11 cm in size and were made up of four pages (or multiples of four), illustrated with woodcuts. They contained tales of popular heroes, legend and folklore, jests, reports of notorious crimes, ballads, almanacs, nursery rhymes, school lessons, farces, biblical tales, dream lore, and other popular matter. The texts were mostly crude and anonymous, but they formed the major part of secular reading and now serve as a guide to the manners and morals of their times.” Thus chapbooks were often “news,” of one sort or another, and almost as often apocryphal or pirated, or both—news that took “poetic license,” one might say, news that, as Pound once said of poetry, “stays news.”